MacSysAdmin Conference is an annual technical conference focused on system administration, management, and security of Apple products, particularly macOS and iOS, aimed at IT professionals, system administrators, and developers. It brings together participants from all over the world to share knowledge, experiences, and best practices within the Apple ecosystem, combining in-depth technical sessions with valuable networking opportunities.

Security is also a recurring theme at the conference, with sessions delving deep into securing Apple platforms in enterprise and educational settings, addressing key areas like endpoint security, device compliance, identity and access management, privacy, zero-trust principles, and incident response. Speakers frequently present real-world security challenges and solutions, ensuring the content’s high relevance for organisations with stringent security and regulatory requirements.

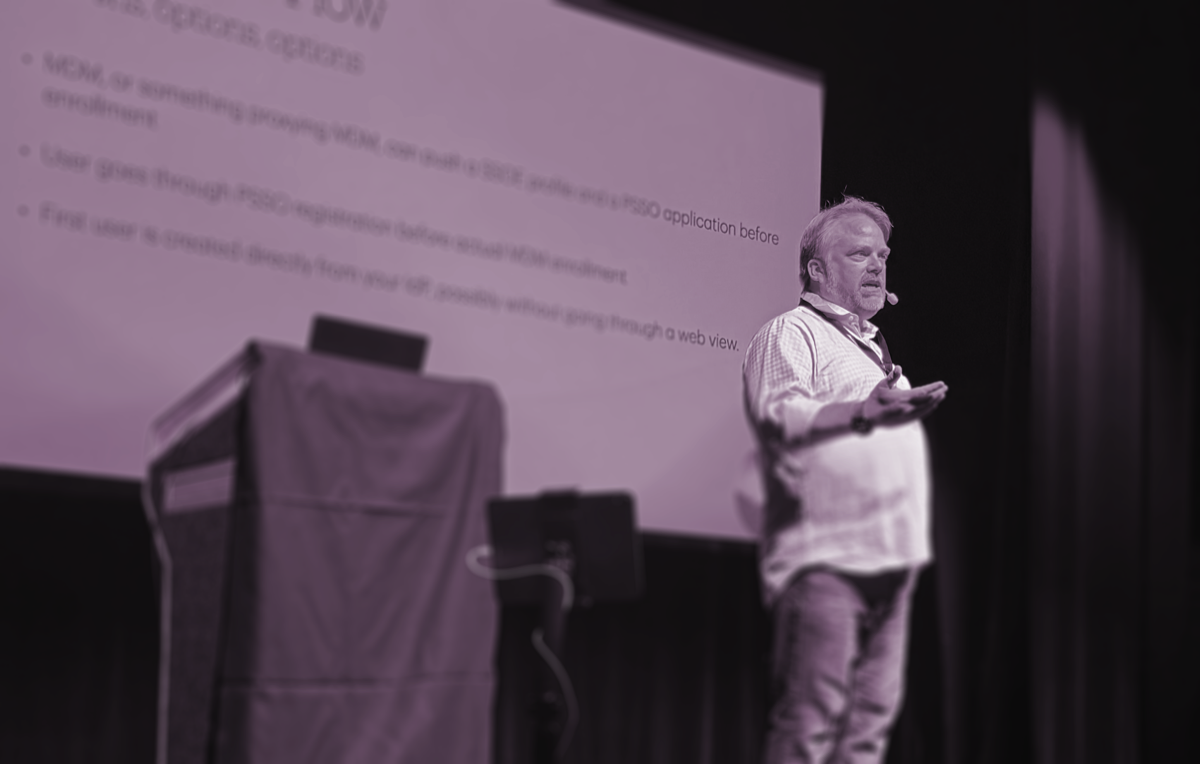

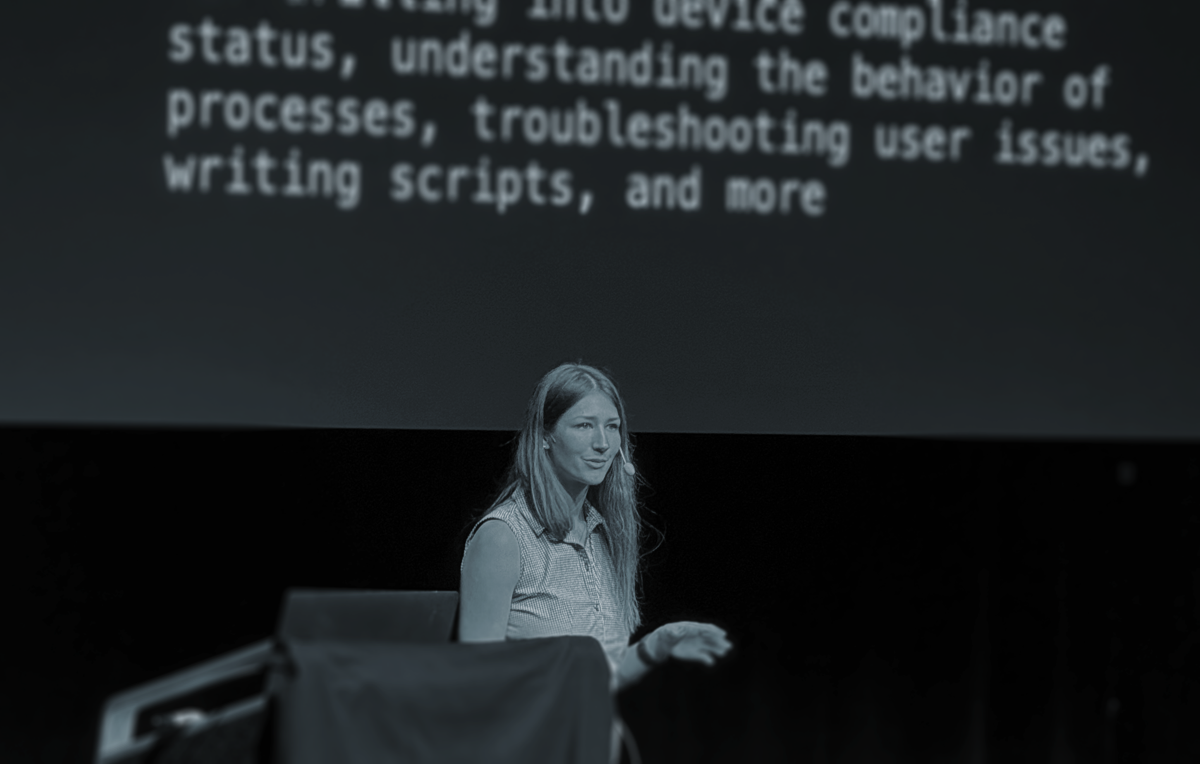

The format is traditionally single-track, meaning that all attendees take part in the same sessions rather than choosing between parallel tracks. This ensures that everyone has access to the entire program without schedule conflicts. The agenda includes presentations, some with live demonstrations covering device management, security architecture, automation, deployment strategies, API integrations, and other practical tools and workflows relevant to Apple administrators.

Speakers at the conference are often highly respected experts and senior engineers within the Apple community, including representatives from leading companies and active members of the global Mac Admins community.

In addition to the formal conference days, MacSysAdmin places strong emphasis on community and networking, with social events, evening gatherings, and informal “hallway track” discussions that encourage collaboration and long-term professional connections.

With its combination of deep technical content, strong security focus, and community-driven atmosphere, MacSysAdmin Conference is widely regarded as one of the most respected and valuable events for Apple system administrators in Europe and internationally.

The full schedule for 2026 will be published later.